Stanley Spencer Gallery

High Street

Cookham

Maidenhead

SL6 9SJ

United Kingdom

Stanley Spencer Gallery is delighted to present Mind and Mortality: Stanley Spencer’s Final Portraits. Comprised of 26 works, the exhibition spans fifty years from 1909 until the artist’s death on the eve of the 1960s and reveals not only the importance of portraiture to Spencer’s artistic practice, but also the intimacy and unflinching candour he brought to it.

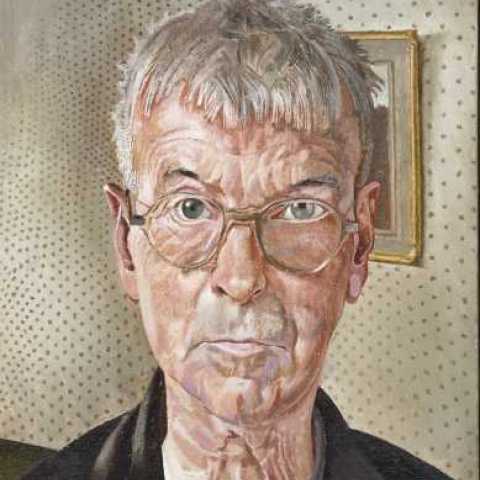

Mind and Mortality, which includes works in oil, drawings, pen and inks and a single lithograph, is formed of three parts: Self-Portraits, Mind, Body and Spirit, and The People and Portraits of Spencer’s Final Years. The cornerstone of the exhibition is Spencer’s two final self-portraits, made when he was dying of cancer, displayed side by side for the first time. The first is a drawing in red conté which was recently acquired by Stanley Spencer Gallery. The other, on loan from Tate, London, is Spencer’s final self-portrait in oil paint. They were commissioned by a friend of artist, who rejected the drawing, probably because she found its unflinching gaze too uncomfortable.

The red conté drawing is the ultimate expression of Spencer’s talent in that it not only a true likeness, but also hints at the uneasy thoughts which must have been at the forefront of a dying man’s mind. The artist’s gaunt, weathered face is overwhelmed by the frame of his glasses. Yet the deep wrinkles of the forehead, the sagging flesh of his neck, and the grim, sloping downturn of the mouth are offset by a determination and strength found in his unflinching gaze.

The presentation also includes Spencer’s earliest known self-portrait from 1912, on loan from the Williamson Art Gallery and Museum Birkenhead, and a drawing of his brother, Gilbert, dated 1909, when Stanley was just seventeen and Gilbert sixteen.

In his final decade, Spencer was in high demand as a portrait painter, and in People and Portraits, the gallery has brought together fourteen works that showcase Spencer’s immense skill in painting and drawing portraits. They include a portrait of Dr Osmund Frank, one of the stars of the 1951 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition and described as a ‘Modern Holbein’ thanks to its meticulous rendition of Dr Frank’s fur robes. Spencer’s sitters were often the family and friends who offered him friendship and support. Notably amongst these is a portrait of Lathonia, the daughter of his Cookham GP Dr Vaudrey Mercer, who invited Spencer regularly to meals as his suffering from cancer worsened.

On loan from the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry, is Spencer’s heart-breaking portrait of Priscilla Ashwanden, the daughter of a neighbouring family, who was dying of leukaemia aged just sixteen. Tragically, the finished portrait arrived at the family home the morning of her death. Priscilla’s diary, in which she describes her sittings with Spencer, will be displayed near her portrait.

The works united under the theme Mind, Body and Spirit help us to understand why Spencer’s portraits might at first appear unflattering, but often express his great love for the sitter. They include gems from Stanley Spencer’s Gallery’s standing collection, including the enormous, Christ Preaching at Cookham Regatta (1952—1959) that he was still working on when he died, The Angel, Cookham Churchyard (c.1936-1937) and Sarah Tubb and the Heavenly Visitors (1933), in which we see the sitter being comforted by angels after the appearance of Halley’s Comet in 1910. One of the works in Mind and Mortality is not by Spencer, but by his talented daughter Unity, who captured the likeness of her uncle Will in a style uncannily similar to her father’s.

Curator Amy Lim says, ‘We’re delighted to exhibit Spencer’s final two self-portraits side by side for the first time. They show off his immense skill as a portraitist and give us an insight into how he confronted his own mortality during his final struggle with cancer. Spencer’s portraits are often overlooked and visitors will have a chance to see for themselves why he was one of the most in-demand portrait painters of the post-war years.’